This Is Ours: Guyana

As a Guyanese expatriate living in the United States for almost thirty-five years, I am always thrilled to return to the country of my birth. On this particular occasion, the excitement was tinged with nervousness.

I was returning with colleagues to teach the This Is Ours curriculum at two very different schools in two distinct regions of the country; my alma mater Queen’s College on the coastal plain, and Bina Hill Institute Youth Learning Institute in the North Rupununi savannah. My entire childhood was spent on the coastal plain of Guyana in the little village of Nabaclis. I did not know much about the culture of the indigenous Amerindian people of the Rupununi. The opportunity to learn more about both regions and its people from the perspective of its youth and to share that with the world was humbling, exhilarating and inspiring. I was their link to the past as they were my connection to the future.

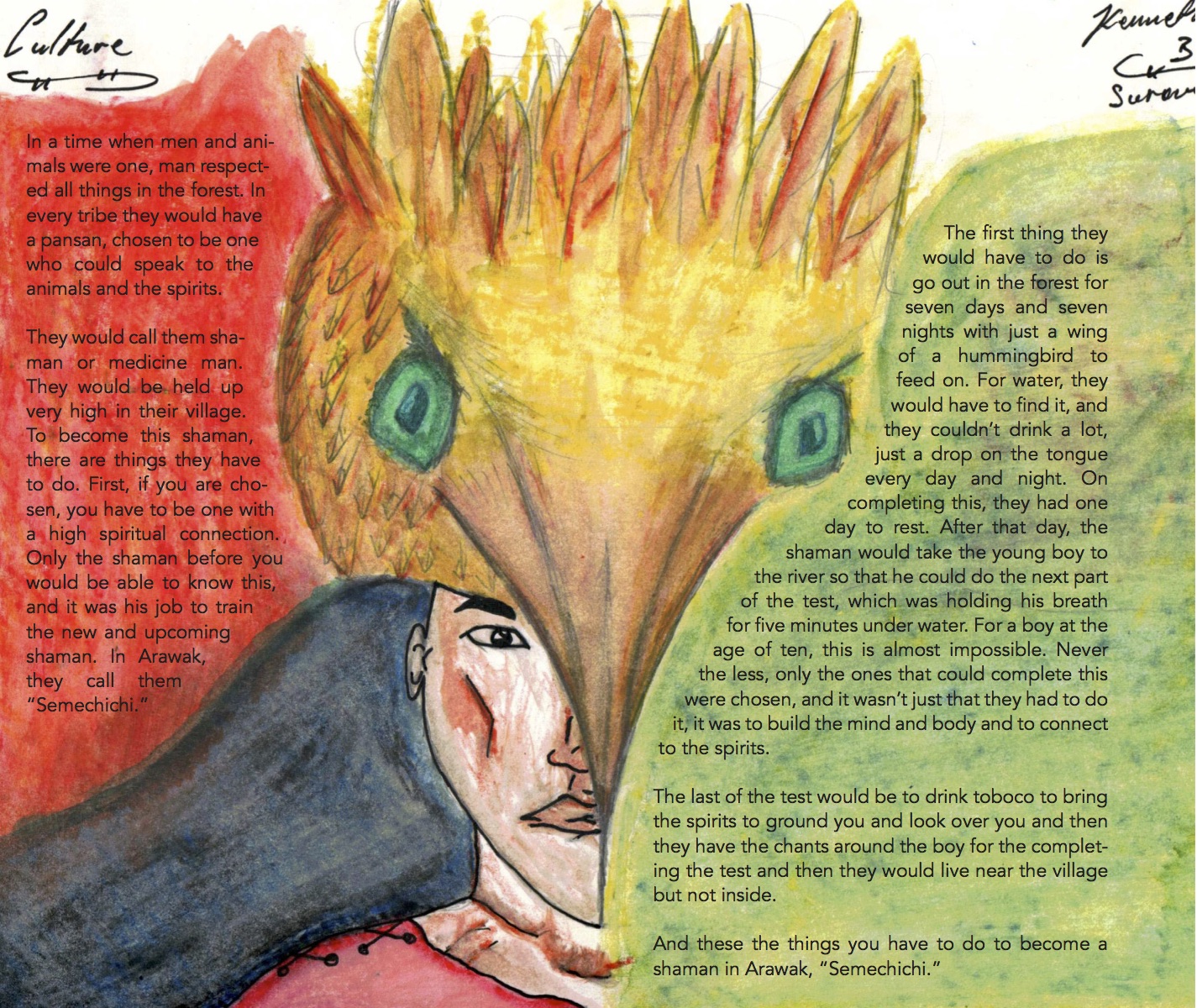

The Bina Hill Institute Youth Learning Center in Annai in the North Rupununi was the first school we visited. To get there, we flew on a “putt-putt” (Guyanese slang for a 15-passenger plane) from the coastal plain over the hilly sand and clay region, and over the forested highlands. We crossed many mighty rivers lined by lush trees from the rainforest. When we arrived at Bina Hill Institute in the vast savannah, patiently waiting for us were nineteen students from the Wapishana, Patamona and Makushi indigenous Amerindian groups. They had prepared an opening program to welcome us that included original songs in English. The songs were moving; the one that most resonated with me spoke of a simple country girl yearning for a chance to reach to the skies. I was moved to tears by their hospitality and even more by the song’s poignant lyrics.

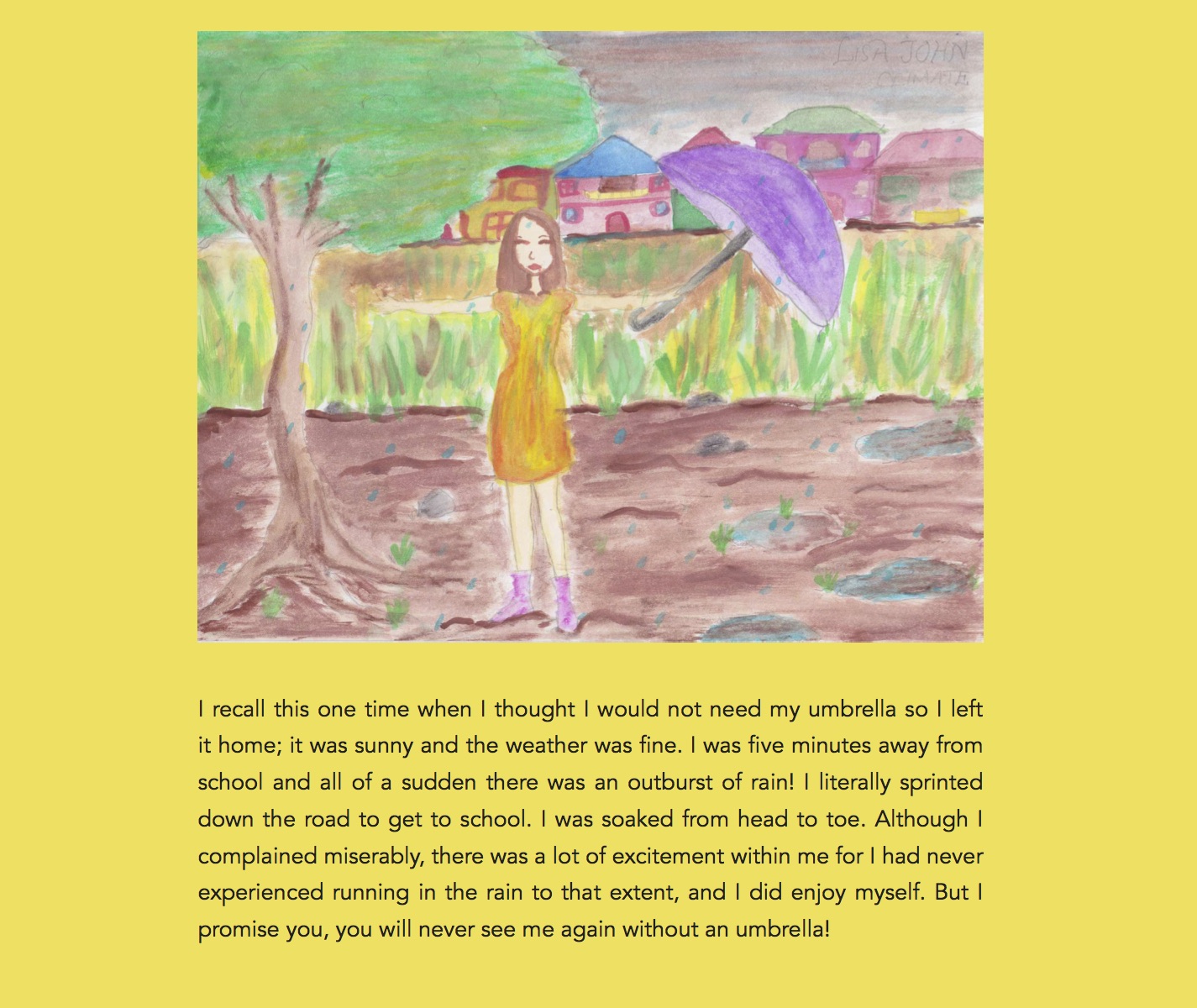

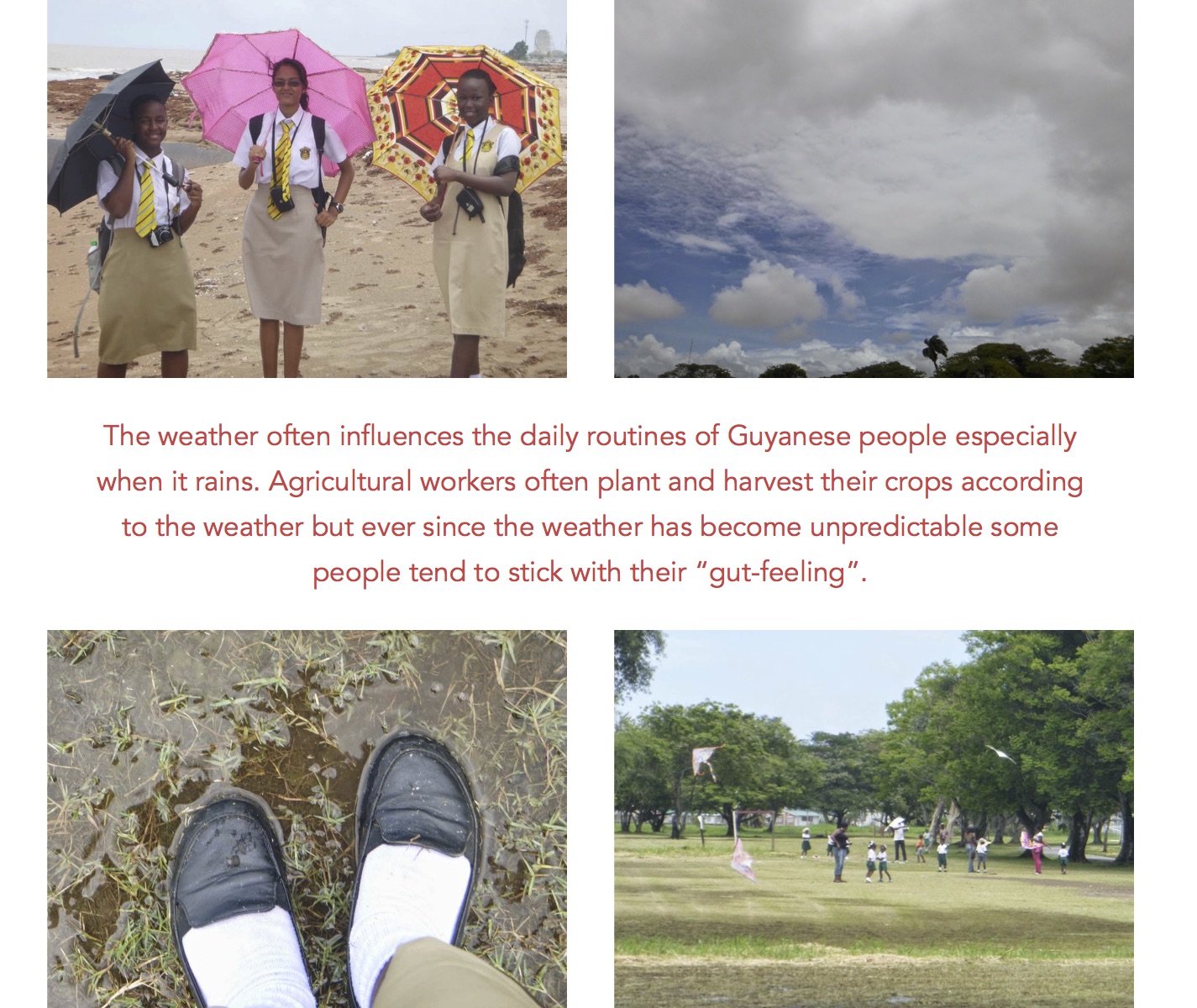

We quickly set about brainstorming and deciding on topics of interest to be covered in the program. Over the next days, we delved into their selected topics and began documenting related stories using illustration, photography, writing and interviewing. They spoke about their culture and the importance of the ecosystem in their traditions. The students reported subsequently that as they intentionally began to document components of their lives and environment, the ensuing conversations unexpectedly piqued their interest in their customs and traditions. They found themselves wanting to learn even more about their deep history. Some expressed disappointment in not being more fluent in their traditional language. Furthermore, while gathering and presenting information on their chosen topics, students experienced one of the unstated though very powerful components of This Is Ours. They began to discover their strengths and resilience. For instance, one student defiantly declared at the beginning of the week that she was no good at painting. During the closing ceremony, she tearfully, proudly and publicly announced that she discovered that she could illustrate and paint. She realized that she “can” if only she tried. In between those markers, the Bina Hill Institute students articulated that climate change was affecting their way of life; they can no longer rely on the traditional calendar that outlined rainy and dry seasons.

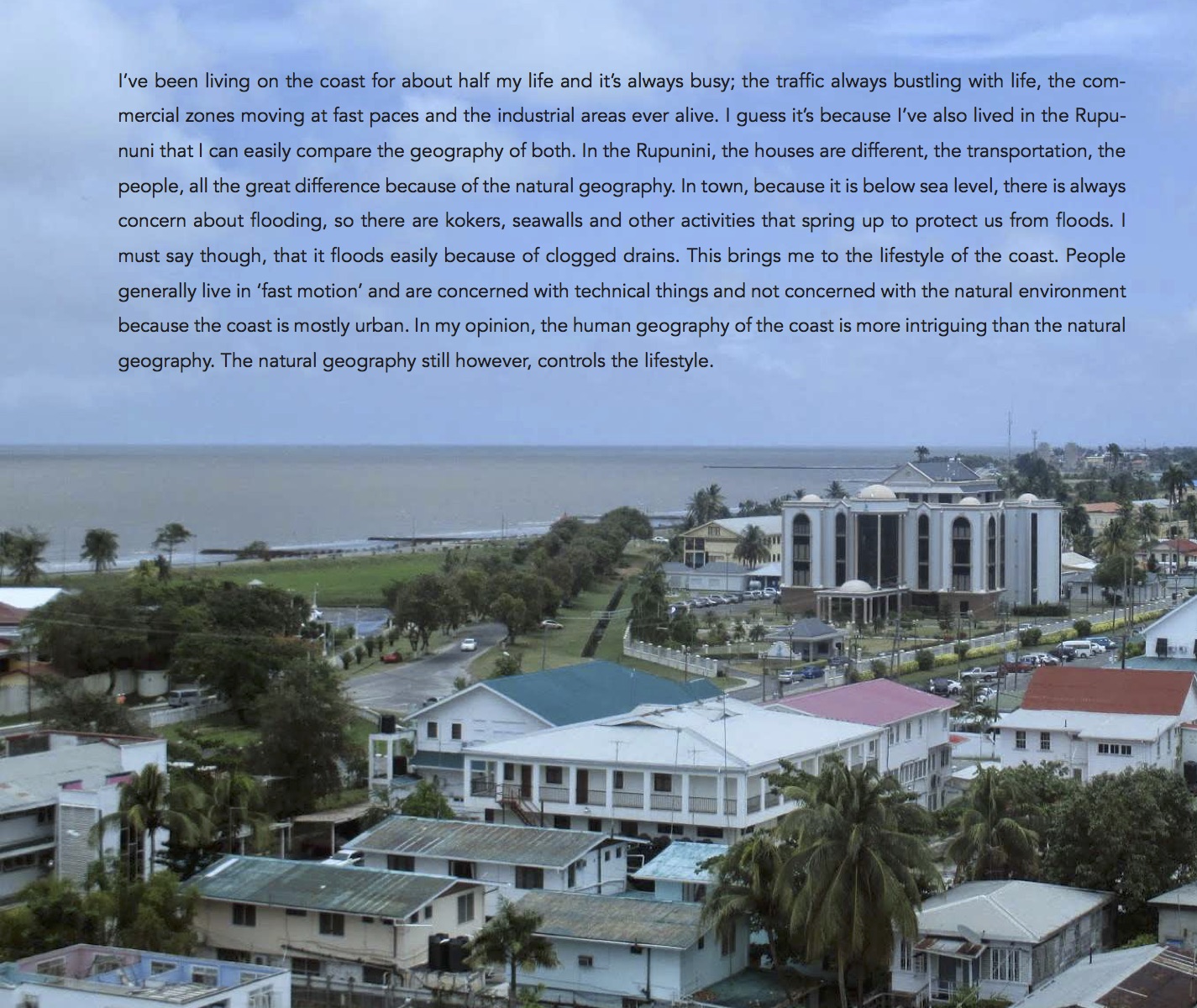

Our second visit was to Queen’s College, in Georgetown, the capital of Guyana. Because two of my colleagues and I are alumnae of this 170-year old secondary school, our visit was a homecoming of sorts. Again, we began with brainstorming in order to determine the areas in which the students would focus. The Queen’s College students decided their This Is Ours would concentrate on coastal geography, water, culture, nature, and climate.

The students at the Bina Hill Youth Learning Centre represented three of the nine Amerindian tribes living in the Rupununi. Similarly, the Queen’s College students population was ethnically diverse. They self-identified as Afro-Guyanese, Indo-Guyana, Amerindian (Wapisahana) and multi-racial. They viewed their racial and cultural differences as a cause for celebration. Their expressions on the many rich cultures of Guyana were insightful and hopeful. Perhaps it was the impending national elections in a nation where voting along racial and ethnic lines has historically been the norm that caused the students to openly and repeatedly long for national unity.

By the end of the week, like at Bina Hill Institute, some Queen’s College students revealed that their experience with This Is Ours was empowering and self-revealing. They realized that they did have important stories to communicate and that they did have a voice. Many reported that the visual literacy program caused them to take stock of their surroundings. Having done so, they found that they were taking for granted the natural beauty of their environment.

While experiences at the two schools were at times completely different, one commonality was that students and I both recognized that regardless of our perceived differences in age, ethnicity, gender and background, what unites and binds us are the things that are ours, the things that are Guyanese, the things that reflect our country’s motto of “One People, One Nation, One Destiny”. In this book, you too will notice how interconnected we truly are in Guyana and in the world.

- Karen Wharton